|

By Jennifer Connolly

September 25th, 2012 One of the key sources of contention in the recent Chicago Teacher’s Union Strike was a proposal by Mayor Rahm Emanuel to change how teacher performance is evaluated. This brings to light one of the central concepts of public management: As taxpayers, how do we, through our government, hold public administrators and teachers accountable for educating our nation’s children? Tax revenues fund public school operations, and public schools are supposed to be an enterprise ultimately working for the public. However, numerous public school systems lack a rigorous mechanism for holding public administrators and teachers accountable for the quality of the job they are doing in educating our children. Mayor Emanuel proposed using standardized test scores to account for as much as 45% of a teacher’s end of year evaluation while the teachers, ideally, wanted standardized test scores excluded from their performance evaluations. In the end, the teachers conceded to allowing test scores to account for no more than 30% of their evaluations. However, is this really the best way to hold teachers accountable for student outcomes? According to this JPP article by Robert Schwartz, a complete school accountability program should include “information about three types of performance: academic achievement, other student outcomes, and teaching processes” (2000). He writes that the standards for judging teacher performance should be based on specified standards, and, that it is also essential for rewards and sanctions (for success and failure) linked to those standards to be consistently provided or imposed. In the U.S., we have historically had both a professional and a hierarchical accountability system, in which American government officials at the federal, state, and local level have passed laws outlining in detail what subjects are to be taught, how those subjects are to be taught, and requiring teachers to earn certain professional certifications. However, this system does not focus on using academic achievement or student outcomes as a way to measure performance. Schwartz writes that for most of our history, the public was generally content with this system of hierarchical accountability, but in the last several decades, there has been a push for external accountability and the incorporation of measures of academic achievement and other student outcomes. So far, this has largely come in the form of publishing school level academic outcomes and allowing for more school choice. However, more recently, as illustrated by the situation in Chicago, there has been a push to hold individual teachers accountable for their students’ academic achievements and other student outcomes. The union and the mayor ultimately came to a compromise to link 30% of a teacher’s performance evaluation to their students standardized test scores. However, there may be more nuanced ways to structure teachers’ incentives in order to lead to better performance and student outcomes. For example, new research by a group of economists looks into the application of the principle of loss aversion to structuring teaching incentives. The researchers conducted an experiment by dividing teachers into three groups: those that got no incentive pay, those that were promised an end of year incentive if their students performed well, and those that were given a $4000 bonus up front, but had to sign a contract promising to return the money if their students did not meet certain standards. The full details of the study are available here, but the researchers found that students whose teachers were given the bonus upfront performed much better on the end of year tests than students of teachers in the other two groups. The teachers who knew they would have to return their bonus were more personally committed to the students’ success and were more likely to repeat a lesson or spend extra time on a topic when they began to detect that students were not understanding or retaining the material. While there is clearly more work to be done to better understand the relationship between teacher incentives and student performance, this research suggests that by thinking outside of the box we may be able to uncover better incentive programs to increase performance and accountability in public schools. Simply telling teachers that 30% of their end of year performance evaluation will be tied to standardized test scores may not be enough.

1 Comment

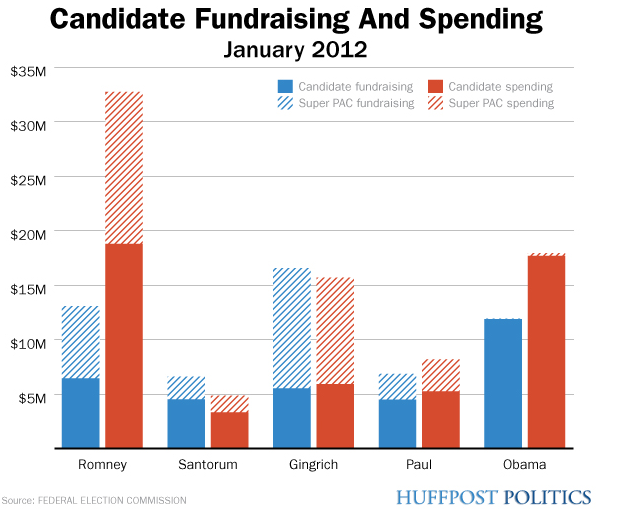

With campaign season in full swing, the media and political analysts of all stripes have been paying a lot of attention to interest groups and their influence on the upcoming elections. The media tells countless stories about interest groups and super PACS and all the money they have raised and spent on the election in the hope of influencing electoral outcomes and policymaking. There have also been reports of trade associations spending vast sums of money this election season. Despite the plethora of anecdotal evidence about one interest group or another, we hear relatively little empirical evidence related to how successful these groups are at pushing their agendas.

In a 2007 JPP article, University of Virginia political scientist Christine Mahoney found that interest groups are more successful at getting what they want in the US than in the EU where politicians are much less dependent on getting money from political donors to finance re-election campaigns. Mahoney recently told me, “One of the big differences we see between the US and the EU is the power of corporate lobbyists. In the US they get more of what they want, more of the time.” However, in the five years since Mahoney’s article was published, the Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission case has changed the rules of the game. The Supreme Court’s decision in the case held that the government could not limit independent political expenditures by corporations and unions. Mahoney predicts that in the wake of this ruling, with corporations and trade associations now free to spend unlimited sums on political messaging, we are bound to see corporate lobbyists getting even more of what they want, even more of the time. As Mahoney wrote, “The design of the political system has implications for the responsiveness of politicians; this in turn fundamentally affects who succeeds and who does not. Specifically, the coupling of direct elections and private funding of elections in the U.S. leads to a system with incentives for elected officials to be more responsive to wealthier actors.” (55). I recently spoke with Mahoney and asked her how the interest group environment has changed in the last five years. Mahoney mentioned that trade associations and corporations are certainly more successful than citizen groups in terms of influencing the outcomes of elections. She told me that, “policymakers behave as if money matters, members from both parties pass legislation that favors tax breaks for oil companies and factory farms while they cut funding for social safety nets.” The influence of corporations will only grow as corporations are now allowed to spend unlimited funding on political advertising and individuals are limited by contribution limits. However, even these contribution limits don’t stand in the way of wealthy individuals. For example, as Mahoney explained, if you consider a large corporation, the CEO can give $2000, the CEO’s wife can give $2000, the CFO can give $2000, the CFO’s spouse can give $2000, and on down the line, until the higher ups at a corporation have given tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars to candidates and political parties throughout the course of the primary and general elections. This money helps politicians win elections, and in return, Mahoney’s analysis shows, policymakers clearly vote in a manner not to offend major campaign donors. Now that the Supreme Court has ruled that the government can’t limit spending by corporations, is there anyway for groups with divergent interests to overcome the spending power of these major corporations? The answer is yes and no. The battle will happen not between corporations and citizen groups, most of which can’t compete financially with corporations, but rather, between corporations. There are a growing number of corporations who are looking closely at the value they create for society and trying to maximize that value; they subscribe to the idea of corporate social responsibility (CSR). Examples include Patagonia, which donates 1% of all profits to environmental causes, or Tom’s Shoes which provides one pair of shoes to needy children for every one pair purchased. Mahoney predicts that if we “celebrate and foster this corporate revolution, in time, we’ll have strong corporate allies for the legions of Civil Society organizations working to protect consumers, the environment, human rights and advocating for other social justice issues.” So although the political landscape will likely continue to be shaped by corporate interests, with the growth of CSR, we may see more of a battle between corporations than between corporations and individual citizens. By Jennifer Connolly

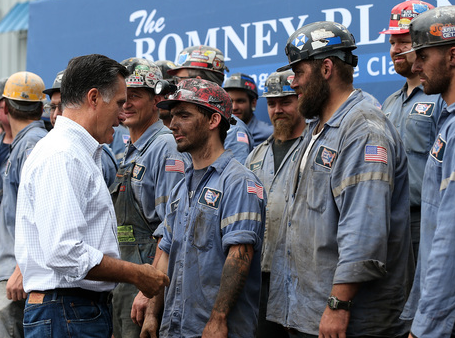

August 17th, 2012 Energy policy is having a surprising moment in the political spotlight in the middle of a presidential campaign that everyone assumed would center on the economy, jobs, healthcare, taxes, and a little more of the economy. Barack Obama and his staff are touting the wind industry as the next great provider of jobs while Mitt Romney is telling anyone who will listen that Obama’s environmental policies are killing jobs in the coal mining industry. The presidential candidates are bringing energy policy to the forefront. But, while the candidates may be using energy policy as their latest way to attack each other and win over swing voters, is Congress likely to implement any drastic changes to energy policy in the near future? Well, as Niels Bohr said, “Prediction is very difficult, especially about the future.” However, we can take a few hints from some newly released scholarly research which suggests that the answer may depend less on who wins the election and more on whether there is a major energy shock (such as a drastic increase in gas prices or a major electricity shortage) to spur politicians to action. Energy policy is highly technical and the costs and consequences of new policies are often rather immediate, or at least evident, within one or two election cycles. Many politicians, in their never ending quest to avoid blame for unpopular or costly policies, don’t really want to touch energy policy with a ten foot pole, so long as there isn’t a major energy shock resulting in continued public outcry for them to “do something.” By Jennifer Connolly

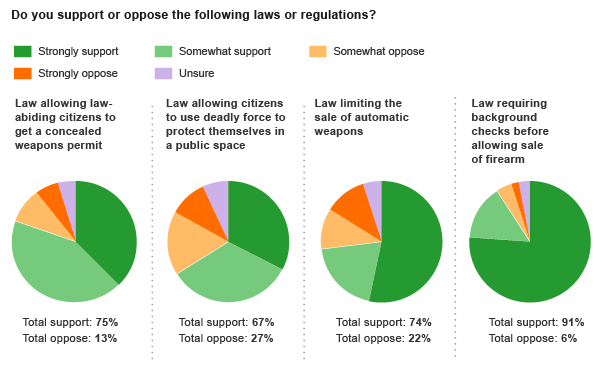

July 23rd, 2012 In the wake of the movie theater shooting in Aurora, Colorado, I have heard many friends, fellow scholars, and journalists question why gun control policy hasn’t evolved to more tightly regulate the public’s ability to purchase and carry weapons, particularly assault style weapons. In the last week, there has been a lively and at times vitriolic debate over how the U.S. should change (or not change) our gun control policies. Regardless of my personal stance on this debate, I have a feeling that advocates for stricter gun control are fighting an uphill battle. I am not a gun control policy expert, and I don’t seek to promote any specific policy position in this debate. As the Editorial Assistant for the Journal of Public Policy, I regularly review past issues of the journal and just last week I came across an article on credit claiming and blame avoidance that sheds some light on the current state of gun control policy and why it isn’t likely to change anytime soon. At first it might seem that politicians, seeking re-election or election to a higher office, would support the policy position supported by a majority of the public, as that would gain them favor with the electorate. But the case of gun control policy offers a stark counterexample to that theory. Polls released in the last few years give every indication that a majority of the public is in support of some form of stricter gun control, yet policy doesn’t seem to reflect public sentiment. For instance, 63 percent of people favor a ban on high capacity magazines or clips (January 2011 CBS News poll), 86 percent support requiring all gun buyers to pass a criminal background check, no matter where they purchase the weapon or from whom they buy it (American ViewPoint/Momentum Analysis poll), and 69 percent support limiting the number of guns a person could purchase in a given time frame (April 2012 Ipsos/Reuters poll). With a majority of the public in support of stricter gun control, and with horrific tragedies like the movie theater shooting in Aurora gaining national attention, why aren’t politicians jumping at the opportunity to pass policies that would more strictly control the sale of weapons? Kent Weaver offers a compelling explanation in this 1986 JPP article. While I highly recommend reading the full article, the basic idea is that, from a politician’s perspective, it is very difficult to effectively claim credit for preventing shootings by passing stricter gun control policies, but very easy to bear the blame for creating a difficult gun acquisition process. While it is difficult for a senator to credibly claim that he prevented a hypothetical shooting from happening in his state because of stricter national gun control laws, his opponents can very easily blame him for creating bureaucratic red tape that complicates and hinders the ability of law abiding citizens to obtain weapons legally. |

About the Blue PencilIn publishing, blue pencils were traditionally used by editors to mark copy. Scholarly research is extremely relevant to current policy debates, but it is rarely edited with the goal of making it easy to understand for the average news consumer. With this blog, Dr. Connolly takes scholarly articles and condenses, summarizes, and recaps them to make them quick and easy to understand. Archives

September 2012

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed