|

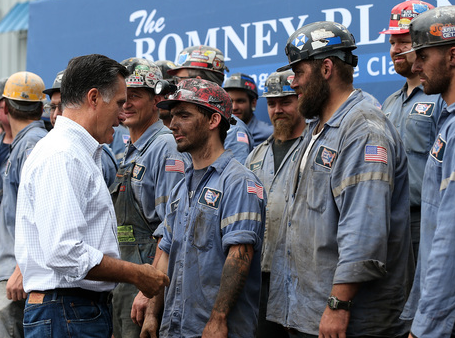

By Jennifer Connolly August 17th, 2012 Energy policy is having a surprising moment in the political spotlight in the middle of a presidential campaign that everyone assumed would center on the economy, jobs, healthcare, taxes, and a little more of the economy. Barack Obama and his staff are touting the wind industry as the next great provider of jobs while Mitt Romney is telling anyone who will listen that Obama’s environmental policies are killing jobs in the coal mining industry. The presidential candidates are bringing energy policy to the forefront. But, while the candidates may be using energy policy as their latest way to attack each other and win over swing voters, is Congress likely to implement any drastic changes to energy policy in the near future? Well, as Niels Bohr said, “Prediction is very difficult, especially about the future.” However, we can take a few hints from some newly released scholarly research which suggests that the answer may depend less on who wins the election and more on whether there is a major energy shock (such as a drastic increase in gas prices or a major electricity shortage) to spur politicians to action. Energy policy is highly technical and the costs and consequences of new policies are often rather immediate, or at least evident, within one or two election cycles. Many politicians, in their never ending quest to avoid blame for unpopular or costly policies, don’t really want to touch energy policy with a ten foot pole, so long as there isn’t a major energy shock resulting in continued public outcry for them to “do something.” However, even if Congress decides to “do something” and overhaul energy policy, it doesn’t necessarily mean they will make rational or effective policies. As Peter Grossman writes in his most recent article published in the Journal of Public Policy, in the event of a major energy shock, “extreme and irrational” legislation would be a likely or even inevitable response to the demand from constituents that political actors “do something.” He describes this type of policy process as one in which the public pressures politicians to act, but they may not take the time to carefully analyze an issue and are likely to pass extreme and irrational legislation. He further expands that in this type of policy making process, precisely because they may not have had time to conduct a technically advanced analysis of the issue at hand, politicians will favor policies and projects for which the outcome and the cost can be defrayed over a long period of time. While Grossman writes that major energy shocks are likely to lead to drastic changes in energy policy in the U.S., the recent surges in energy prices have been small enough that consumers and their representatives have been able to tolerate them. Put simply, the prices haven’t risen quickly enough, to high enough levels, and they haven't stayed high enough to elicit the type of constituent outrage that makes politicians feel that they have no choice but to address the issue. This helps explain why both presidential campaigns are focusing their attention on energy policy only so far as it concerns the creation (or destruction) of jobs, rather than engaging in a more in-depth discussion of energy prices. For any sort of significant change to energy policy to occur, we would likely need a major energy shock to spur legislative action. It is important to note that this isn’t true of just energy policy, however. Grossman recently told me that, “Any event that produces a sense of crisis is likely to lead to demands for political actors to ‘do something.’ With some types of crises – for example, the 2008 financial crisis – there is a sense that the something should be done quickly and at a great cost, leaving some legislators vulnerable in the next election cycle.” As Grossman’s article further explains, most legislators would prefer to pass policies for which the costs and any measurable outcome can be put off into the future. In fact, when considering a policy such as TARP, the costs were immediate and the outcomes were quickly apparent, contributing to several Congressmen losing their seats over their support of or opposition to the program. This is exactly why it is unlikely that Congress will take any major action on energy policy without some sort of major energy shock and widespread constituent demand to “do something.” So, while those of you who are proponents of making major changes to energy policy might be encouraged by the presidential candidates’ increased attention to energy policy, I wouldn’t expect major legislative changes anytime soon. Obama and Romney are really trying to reach voters with a message about jobs, and the energy sector just happens to be a good tool for them to use to make a point. For the US Congress to make any significant shift in energy policy there would likely have to be a much more severe energy shock than any we have seen recently, and if that happens, we might not like the policies that come out of Congress during crisis mode. Note: Grossman’s model of the policy making process is largely presented through the lens of energy policy, however, it can be applied to any sort of crisis, whether it be a financial crisis or a national security crisis. Grossman told me that he plans to further expand this line of research by comparing the US experience with those of other democracies to, “see if what [he] has observed is peculiar to the US system, or to first-past-the-post electoral systems, or to any electoral system including proportional systems.” If you are interested in this line of research, I encourage you to read the article here, and to keep an eye out for Grossman’s new book, “US Energy Policy and the Pursuit of Failure,” which is to be published by Cambridge University Press next year.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

About the Blue PencilIn publishing, blue pencils were traditionally used by editors to mark copy. Scholarly research is extremely relevant to current policy debates, but it is rarely edited with the goal of making it easy to understand for the average news consumer. With this blog, Dr. Connolly takes scholarly articles and condenses, summarizes, and recaps them to make them quick and easy to understand. Archives

September 2012

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed