|

By Jennifer Connolly

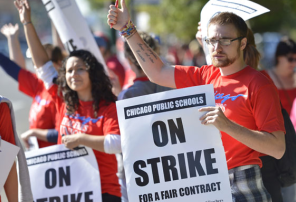

September 25th, 2012 One of the key sources of contention in the recent Chicago Teacher’s Union Strike was a proposal by Mayor Rahm Emanuel to change how teacher performance is evaluated. This brings to light one of the central concepts of public management: As taxpayers, how do we, through our government, hold public administrators and teachers accountable for educating our nation’s children? Tax revenues fund public school operations, and public schools are supposed to be an enterprise ultimately working for the public. However, numerous public school systems lack a rigorous mechanism for holding public administrators and teachers accountable for the quality of the job they are doing in educating our children. Mayor Emanuel proposed using standardized test scores to account for as much as 45% of a teacher’s end of year evaluation while the teachers, ideally, wanted standardized test scores excluded from their performance evaluations. In the end, the teachers conceded to allowing test scores to account for no more than 30% of their evaluations. However, is this really the best way to hold teachers accountable for student outcomes? According to this JPP article by Robert Schwartz, a complete school accountability program should include “information about three types of performance: academic achievement, other student outcomes, and teaching processes” (2000). He writes that the standards for judging teacher performance should be based on specified standards, and, that it is also essential for rewards and sanctions (for success and failure) linked to those standards to be consistently provided or imposed. In the U.S., we have historically had both a professional and a hierarchical accountability system, in which American government officials at the federal, state, and local level have passed laws outlining in detail what subjects are to be taught, how those subjects are to be taught, and requiring teachers to earn certain professional certifications. However, this system does not focus on using academic achievement or student outcomes as a way to measure performance. Schwartz writes that for most of our history, the public was generally content with this system of hierarchical accountability, but in the last several decades, there has been a push for external accountability and the incorporation of measures of academic achievement and other student outcomes. So far, this has largely come in the form of publishing school level academic outcomes and allowing for more school choice. However, more recently, as illustrated by the situation in Chicago, there has been a push to hold individual teachers accountable for their students’ academic achievements and other student outcomes. The union and the mayor ultimately came to a compromise to link 30% of a teacher’s performance evaluation to their students standardized test scores. However, there may be more nuanced ways to structure teachers’ incentives in order to lead to better performance and student outcomes. For example, new research by a group of economists looks into the application of the principle of loss aversion to structuring teaching incentives. The researchers conducted an experiment by dividing teachers into three groups: those that got no incentive pay, those that were promised an end of year incentive if their students performed well, and those that were given a $4000 bonus up front, but had to sign a contract promising to return the money if their students did not meet certain standards. The full details of the study are available here, but the researchers found that students whose teachers were given the bonus upfront performed much better on the end of year tests than students of teachers in the other two groups. The teachers who knew they would have to return their bonus were more personally committed to the students’ success and were more likely to repeat a lesson or spend extra time on a topic when they began to detect that students were not understanding or retaining the material. While there is clearly more work to be done to better understand the relationship between teacher incentives and student performance, this research suggests that by thinking outside of the box we may be able to uncover better incentive programs to increase performance and accountability in public schools. Simply telling teachers that 30% of their end of year performance evaluation will be tied to standardized test scores may not be enough.

1 Comment

10/1/2013 11:24:21 am

Obstacles don't have to stop you. If you run into a wall, don't turn around and give up. Figure out how to climb it, go through it, or work around it.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

About the Blue PencilIn publishing, blue pencils were traditionally used by editors to mark copy. Scholarly research is extremely relevant to current policy debates, but it is rarely edited with the goal of making it easy to understand for the average news consumer. With this blog, Dr. Connolly takes scholarly articles and condenses, summarizes, and recaps them to make them quick and easy to understand. Archives

September 2012

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed